Enol was walking around Wimbledon, London, in April 2020 when he received a WhatsApp call by Igor from Madrid.

The photos accompanying the interview have been provided by Enol. The cover image has been taken by Jason Lewer.

Hailing from Gijón, a coastal town in northern Spain, Enol García is a recent graduate from London College of Fashion. I met Enol at that same town — he was still in high school, but knew he wanted to be a fashion designer; I was studying industrial engineering and my profesional life was unclear. Fast-forward 13 years — we’re in coronavirus lockdown — and we’re having a call to chat about his final year project at university.

It was last Christmas in Gijón when Enol first told me about his graduate collection, composed of garments made of different ‘blocks’ that can be transformed into many wearable pieces. An innovative approach to sustainability that we discuss in detail in the following conversation.

Igor Termenón

Enol García

You’re on a walk outside, what are you wearing?

I’m wearing my mum’s vintage denim jacket with a white t-shirt and linen Burberry trousers that I got at Riquirraque1 [laughs].

What are some of your earliest memories of fashion?

Both my grandma and her sister are tailors. When I was a kid, I would see how they’d make clothes from two-dimensional things. They would first make patterns using paper and then cut the fabric, turning something flat into something that was three-dimensional — I was always amazed by that.

I used to look at them because they were making those clothes for me. They would measure me and I didn’t understand what was happening — I guess that’s how I got into making clothes.

Both my grandma and her sister are tailors, and when I was a kid I would see how they’d make clothes from two-dimensional things.

I remember when we met — not sure how old you were, maybe 17? — you were preparing for a fashion competition with our now common friend Ornella.

I met Ornella during my last two years of high school. We both studied art and she had just gone back to Gijón from Barcelona, after studying a fashion course there. We started talking about fashion and that’s how we bonded — I wanted to be a fashion designer at the time and she did as well.

She knew about this place where you could learn pattern cutting and that’s how we found out about the competition. We talked to the organisers and they told us it was possible for us to participate and make a collection, but we had to do it in just one month. So we asked our parents for permission not to attend high school for a month. I was making the collection in the mornings in Oviedo and then going back home to Gijón to do all my homework.

Is there anything from that first collection that remains in your current aesthetics or references?

Not really. That collection was a mix of my aesthetics when I was a teenager2. It was all black and very kind of rock ‘n’ roll. It was fun to do and it was educational for me, I guess. Because, who has the opportunity to do a collection when you’re 17 with your best friend?

If I had to make a collection of 8 looks on my own now, I know it would definitely take me longer than a month.

I was studying English in the afternoons and learning pattern cutting in the mornings. I took two pattern cutting courses in a year and that helped me get prepared for my degree.

Going back to pattern cutting. After high school, did you take more courses?

I finished high school and, after that, I wanted to apply to courses in London — that’s where I wanted to study. I found out that I had to apply many months in advance, so I ended up having a whole gap year. I was studying English in the afternoons and learning pattern cutting in the mornings. I took two pattern cutting courses in a year and that helped me get prepared for my degree.

I was asking about this because it is connected to your final year project at university, which heavily revolves around pattern cutting.

Yes, I think it makes much more sense if I explain how I got there from my previous projects at uni.

Please, go ahead!

In my first year, there was this competition organised by H&M, in which you had to create a sustainable collection. It was a group project and my group ended up being one of the winners.

My idea of sustainability was to make these huge, versatile garments that could be fastened in many ways, so you can create different silhouettes.

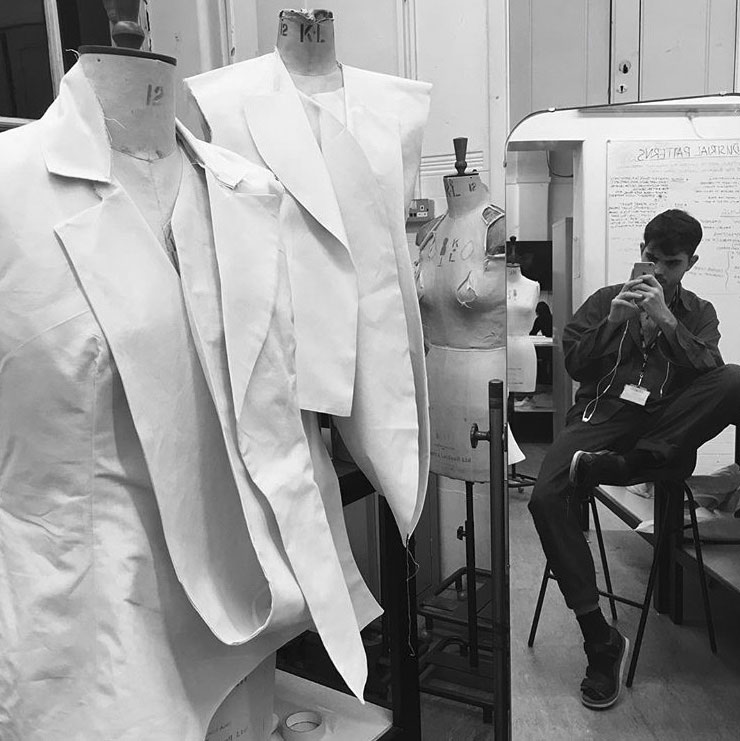

For my second year, we had another competition called ‘The Muse Project’, in which the tutors would choose a muse and you had to create clothes for them. It was a tailoring project and I made a bespoke tailored outfit for a gender-fluid person, who felt more masculine during the day and more feminine in the evenings, when they would perform as a drag queen.

I wanted to create something that would tell their story and I made a tailored jacket, in which one of the lapels could be used as a kind of breast binder and could also be worn in different ways. That’s how I started thinking about tailoring as something that could be versatile as well.

My idea of sustainability was to make these huge, versatile garments that could be fastened in many ways, so you create different silhouettes.

Basically, you were using two different techniques, but you were creating clothes that could be worn in different manners.

Exactly. Between my second and third year, during my summer break, I kept thinking of ways to turn this into a radical statement. One of my main references has always been Margiela — the deconstruction of the clothes and thinking outside the box, without making something that feels very intellectualised or snobby.

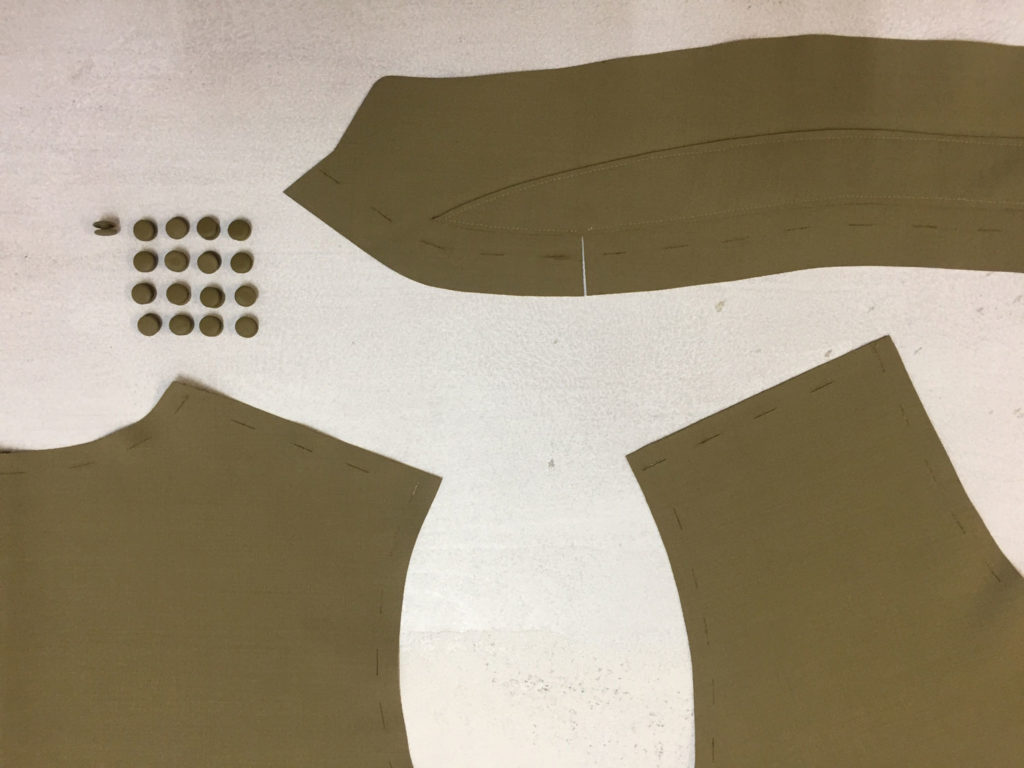

I started thinking about my grandma and my great-aunt again, and how they would make pieces of clothing from patterns. So, I started to look at pattern blocks and all of those elements that compose simple garments; such as the front and back panels of a trouser or the sleeves of a shirt.

So, you were deconstructing regular clothes and iterating these pattern blocks to see how you could create different garments?

Basically, when I was looking at Margiela and people that did deconstruction in the 90s, you would see things like trousers turned into a dress but, at the end of the day, it was just a dress because you couldn’t wear it as a trouser.

So, I thought, what if I make a trouser that is not sewn together and you can deconstruct at home if you want to, and wear it as a dress or as a top, or as sleeves? You can use these pattern blocks as pieces from a puzzle — I hate this term, but I guess you can call it ‘modular fashion’.

I thought, what if I make a trouser that is not sewn together and you can deconstruct at home if you want to, and wear it as a dress or as a top, or as sleeves?

It’s interesting because you’re turning the consumer into a designer, in some kind of way.

Exactly! When I created that first collection with my friend Ornella — when I was a teenager — I had this dream of becoming someone really big in fashion. At the time, you would see Alexander McQueen or Galliano, and how they would be praised after their shows, as if they were superstars3.

I had to work for a lot of years before starting university, and I guess that I moved on from that dream. Now, I see fast fashion and designers that make 4 or 5 collections a year as something very arrogant. With the help of stylists, they’re basically telling people how to wear clothes.

I decided I wanted to design garments that can be taken apart, whilst removing myself from the creative process, so people can end up wearing them however they want. For me, it’s about the response to my garment rather than telling you how you should wear it.

I see fast fashion and designers that make 4 or 5 collections a year as something very arrogant. With the help of stylists, they’re basically telling people how to wear clothes.

I hadn’t thought about it that way, but it’s really interesting to hear the rationale behind it.

I’m currently working on my portfolio to apply to an MA, and I hope I can continue working on this idea.

Now that the technique is a little bit more refined, it would be nice to see different projects merging together, and maybe getting different people involved in a shoot to see what they would do with my garments. I’m pretty sure they’re gonna do some stuff that I don’t like, but that response is even better than if they did something that I would normally do.

For me, it’s about the response to my garment rather than telling you how you should wear it.

Right now, based on what you’ve made for your final year project, what are the limitations in terms of the number of garments you can create?

My collection was quite small, but it took me a long time to get to the technicalities of it and get them right. It was a long and difficult process — I actually failed the first half of my last year.

Both my tutors called me crazy and said it was something that couldn’t be done, but I’m really stubborn and told them that this was something I wanted to try. There was nothing else in fashion that would excite me anymore, and I didn’t want to do a pointless collection of clothes that was going to be out of style in 3 months.

If you use buttons and buttonholes or velcro, or any type of fastening that you can think of, there’s going to be a male and female piece that can be connected together — that limits the options and the amount of blocks you can connect at the same time.

I had to rethink this and created a technique that would allow me to connect more of these elements together. I don’t have a definitive number but, if you want to create ‘conventional garments’, with a pair of trousers you can make a dress, a top, a really cool jacket… But you can also come up with something more abstract.

There was nothing else in fashion that would excite me anymore, and I didn’t want to do a pointless collection of clothes that was going to be out of style in 3 months.

So you can go for the traditional pieces we’re used to wearing, or you can create something more unconventional.

Exactly. I created conventional pieces, but I also made some interesting pieces that I couldn’t really define — they are clothes that cover your body, but there isn’t really a name for them.

How do you see this turning into a business model?

I think there’s a gap in the market and this could work. I need to consider how much money it would take to make these pieces, but I’d like them to be accessible pricewise. I see my customer as someone who is against fast fashion and doesn’t want to have 30 different kinds of trousers, for example. They just need a few pieces that can be worn in different ways.

It would be interesting to see the response I would get if I was just selling the clothes as they are, rather than as separate pieces. And this would make sense in terms of a business strategy, because you would need to get more of these pieces, in order to be able to create even more garments. But, I can also consider just selling these pieces separately, with a platform where people could share the different garments they create — this would also be really interesting.

I see my customer as someone who is against fast fashion and doesn’t want to have 30 different kinds of trousers, for example. They just need a few pieces that can be worn in different ways.

I’ve been asking this to everyone I’ve been interviewing in the past few weeks. How do you think consumer habits are going to change after COVID-19? Do you think people are actually going to slow down and reconsider what they’re buying, or do you think we’re gonna go back to where we were before?

I have friends who are really optimistic and think this is going to create a major change. I hope so, but I’m a realist and we, humans, never learn from our mistakes. There’s going to be a small change, but I’d like the fashion industry to understand that the models we had before are deeply unsustainable.

What I would hope the fashion industry does from now on is producing less and better things, focusing on pieces that last longer. It’s actually a very interesting time to be alive — it might take a while, but I think we will see some change.

1. Charity shop Riquirraque fulfilled Enol’s fashion needs while growing up in Gijón, northern Spain.

2. Some of teen Enol’s references include Miuccia Prada, Dogma 95, indie rock, fencing, grunge aesthetics and muses such as Edie Sedgwick, Cory Kennedy, Kate Moss and Maja Ivarsson, lead singer of Swedish band The Sounds.

3. ‘Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of Alexander McQueen and John Galliano’ by fashion writer Dana Thomas analyses the careers of 2 of the most well-known designer superstars.