Jacqui Burger from SOGOODTOWEAR was interviewed by Igor Termenón at the label’s showroom in Rotterdam on a rainy morning in March 2020.

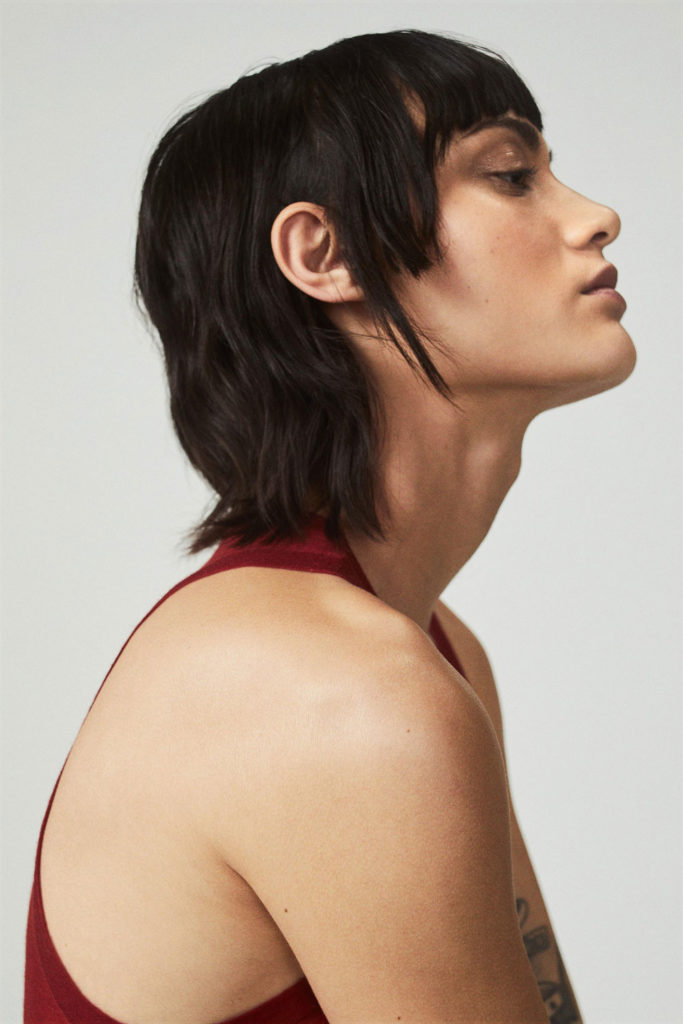

All the pictures used in this article are courtesy of SOGOODTOWEAR.

This is a conversation about goats. This might seem obvious when interviewing a cashmere label, but I wasn’t expecting a story about building a farm in Nepal after the 2015 earthquake, flying Australian goats to this country in made-to-measure crates or creating a new breed, named after the god of goats.

What is even more surprising is that Jacqui Burger, one of the founders of SOGOODTOWEAR, didn’t have any experience at all in the fashion industry before embarking on this fascinating adventure.

Let’s start telling me about yourself and your experience before founding SOGOODTOWEAR.

I’m one of the founders of Good to Give, a company that supports entrepreneurs in third world countries. We’ve been running it for the past 13 years and we help entrepreneurs, who have a business plan, but don’t have access to financial help.

For instance, in Bolivia there’s this guy who wants to start a glass factory. We discuss his business plan with him, all the fair trade and sustainable principles, and then we place an order that can be delivered to us from 1 to 3 years. In the end, he has turnover instead of a loan, and we also introduce his products to the European and Western markets.

In Holland, it’s common for companies to give gifts to their employees at certain times, such as Christmas. Good to Give supplies gifts 1 to a lot of organisations here in Holland and also some in Belgium and Germany. We think that it’s ‘good to give’, when you give someone a gift that it’s also good on a global scale. The nice thing is that every gift comes with a story.

How did this lead to starting SOGOODTOWEAR?

In 2014, my husband and I decided to take our children on a world trip. My mother-in-law passed away and she loved to travel all around the world. She left some inheritance and we thought: “what can we spend this money on to commemorate her?”. We decided to follow one of her biggest passions and travelled to different countries to visit some of the projects we had funded, so our children could see what our work was like.

One of the projects we worked with was in Nepal, and while we were there we went to the far west. I’ve never seen anything so beautiful in my whole life, it’s high up in the mountains and it has all kinds of wild animals that live nowhere else in the world. It was just beautiful and, when we got used to the scenery, we discovered that it was all women and there were no men. We got curious and we found out that most men were working abroad in Dubai, Saudi Arabia, India… they were working as contractors but were illiterate, so they signed contracts that they couldn’t read, which meant they had to work for years before they could get their passport back.

So behind this beautiful, idyllic scenery there was a disaster going on, because there was no economic perspective in the whole region. We wanted to change this and see if we were able to create business opportunities without harming the ecosystem. We found out there was this white stuff hanging in the bushes and it turned out to be cashmere 2.

In Nepal there were still remains of the cashmere goats, but there wasn’t a big quality breed as they had been mixed with the local goats, because there weren’t opportunities to support the cashmere industry in the region.

Did you know that this was a region with the right conditions for cashmere goats before you got there?

No, it was completely by chance. We don’t come from a fashion background, only as consumers. We decided to look for more information and found out that the cashmere industry was there a long time ago and had been a tradition in Nepal, producing a fine type of cashmere wool known as pashmina. They used to comb the Winter fur in Spring — this fur is very insulating and they had a wonderful tradition of making fine fibres. When you only use the undercoat of these cashmere goats, you can knit it really thin and it still keeps all of its properties.

After finding out about this, we thought we could do something related to the cashmere industry. We then knew that the whole cashmere industry was located in Kashmir, which is partly China, India and a bit of Mongolia. In Nepal there were still remains of the cashmere goats, but there wasn’t a big quality breed as they had been mixed with the local goats, because there weren’t opportunities to support the cashmere industry in the region.

Before this, we had already worked on a project in Nepal, not with our own goats but with imported animal-friendly cashmere, producing scarves for a company. We had ordered lots of scarves to see how the production capacity was in Nepal. These first scarves that we made were such a success for Good to Give, that we decided to give it a try and that’s how SOGOODTOWEAR started.

And that’s when you decided to bring back the cashmere industry to Nepal?

In 2014 everyone told us that it was not possible because cashmere goats have to live really high in the snow, in order to get this beautiful quality of winter fur. And then we discovered that there are cashmere herds in Scotland, Australia and even in Tuscany 3.

We embarked on an adventure to bring cashmere goats from these countries to Nepal and interbreed them into a new local breed in 2015. When we were planning this, the April 2015 Nepal Earthquake occurred and we decided to start our goats farm in the region where the epicentre was, Gorkha. A gorgeous region where there was no stone left on top of the other — the earthquake was so severe.

We first bought cashmere goats in Tuscany and we started a farm with female Nepali goats in Bhaktapur, the region where some of the most famous temples are. After a year of preparation — we had vets going to this region to investigate if the goats had any diseases, we made the goats in Tuscany eat Nepali food and so on — the whole project failed.

The Italian bureaucracy demanded a form from Nepal. The Italian goats had to be checked on before they could be imported, but this had never happened before. This went on for around 8 or 9 months and, in the meantime, we had bought those goats and we were feeding them, taking care of them… so at the end we decided to sell them.

We embarked on an adventure to bring cashmere goats from Italia and Australia to Nepal and interbreed them into a new local breed in 2015.

Sorry to interrupt, but it’s so inspiring to hear how you decided to embark on this with no previous experience at all…

I think that was the only way. Anyone with any experience in this field would have said no. By the time we started cursing and saying, “why did we do this?”, we already were quite deep in it and had to go on.

After failing with the Italian goats, we thought about Australia 4. The country has connections with Nepal, because Nepal had imported sheep. And for some reason — I don’t know exactly what happened — someone mistook the word sheep for goats and then, there they were!

They had to be flown from Australia to Nepal, so every buck had a made-to-measure crate in which they could move and someone had to accompany them — it was an incredible adventure. They arrived in Nepal in the middle of the night and no Nepali had ever seen this happening! At the farm, all the female goats were already walking around, and then the Australian goats arrived (6 bucks and 2 females). When the crates opened, they jumped over the fence! Luckily, they were white and easy to spot — there were around 16 Nepali chasing them and they managed to recover all of them.

Anyone with any experience in this field would have said no. By the time we started cursing and saying, ‘why did we do this?’, we already were quite deep in it and had to go on.

Did you get any help during this whole process?

We met with this wonderful Nepali professor from Kathmandu University, whose dream was to create a new breed of cashmere goats and we also had cooperation from the Nepali government.

We had all planned for the breeding and it was so funny — the goats from Australia turned into these big, fuzzy things because the humidity in Nepal is really high; so instead of white, long hair they had giant afros. The Nepali were also really taken aback because the local goats were much smaller and these were huge, especially when they go on their back feet.

We had a goat shepherd who was there with his wife and kids to run the farm, but now his wife is the shepherd because she can manage the goats and he’s really scared [laughs]. That suited us really well because we have fair trade regulations in the company, and we have equal amounts of men and women, and in Nepal this is very unusual.

We now have many goats and the other thing we were doing, in the meantime, was investing in the production facilities. We still import animal-friendly, fair produced wool because we want to have our production up to speed. We expect that within 6 years, we can do everything in Nepal with our own wool. At the moment, we’ve started doing it with some pieces.

We had a goat shepherd who was there with his wife and kids to run the farm, but now his wife is the shepherd because she can manage the goats and he’s really scared [laughs].

When did you launch your first collection?

We launched it in Winter 2016 and, since then, we have been working really hard to improve the production capacity. Especially during the first collections, we had to teach our workers everything.

You didn’t have any background in fashion, why did you decide to start a fashion label?

Because it was the best way to show that Nepal can be a cashmere producing country, including not only the cashmere itself, but also the wool and the manufacturing. It had already happened a while ago, but at a very low scale and it was a different approach.

We knew that our product needed to be high-end because when you have fair trade 5 and completely animal-friendly policies, you need to have a high price. So we knew that in order to convince other high-end brands that your wool and your production is up to their standards, you have to somehow show them. We thought, we’ll just prove it and start our own fashion brand.

We’ve received a lot of help along the way .Some of the fashion buyers were so taken by the story behind the label, that they were advising us on how to improve our product. We started doing everything ourselves and we now have a real fashion designer who knows his stuff, so obviously the brand has evolved.

Starting SOGOODTOWEAR was the best way to show that Nepal can be a cashmere producing country, including not only the cashmere itself, but also the wool and the manufacturing.

How would you define your products?

We are really making wardrobe essentials. We have a collection of 24 items that we present each season — some of them are for men, some of them are for women, and the majority are gender fluid. We try to make things that are gender fluid, not gender neutral, so they look different on a woman or a man but they can be worn by both.

Every season we bring out 3 to 5 seasonal editions that are really eye-catchers. Sometimes one of these can become really popular and can end up being incorporated into the basics collection. And we also produce some of our essentials in a seasonal colour.

The label is currently growing a lot and you are keeping quantities limited. Do you see this as a barrier for the growth of the business?

We will always remain small scale because we don’t believe in fast fashion. We think that the stores can invest in your seasonal items and a little bit of the basics collection, and this collection is basically never out of stock, so if they sell out they can reorder it. They don’t have to invest lots of money in a product without knowing if it’s going to sell well.

We also prefer not to be on sale, because we believe we’re offering a fairly made product which is a wardrobe investment. It’s obviously cashmere and some of the products are really tender and can end up getting holes in them. For one of our lookbooks we decided to have a front cover with a picture of a piece that had several holes, in order to show that if you wear it a lot, it might end up like this. So that it’s either something you embrace or you want to have it repaired, which we also do.

We will always remain small scale because we don’t believe in fast fashion.

I was just going to ask about this, because several brands are starting to offer this service…

This is something that we have under debate. We are growing and the repairs are also growing, so we collect these items and take them to Nepal. And we’re really investigating if we can do this in the Netherlands or another country in Europe.

We try to do everything in Nepal and we have just introduced our new packaging made of waxed paper, so we don’t need plastic anymore.

One of the main issues with brands that are moving towards a more sustainable ethos is online shopping and shipping. How does this affect your label?

We really support the stores that sell our brand because we think that they’re a really important part of the atmosphere and ecosystem of a city. Everybody wants to buy online but they also want to have that convenience store they can go to. If you want that, you have to invest in it.

We do have an online shop but our main goal is to have more stockists, because they are your ambassadors and are so important for the cities.

How else do you contribute to sustainability and social responsibility?

We try to be a B Corporation 6, which means that we have sustainable rules. For example, our director can’t earn so much more than the lowest paid person within the organisation. That puts us in a lot of challenges, because when we do a photoshoot we won’t pay a model thousands of Euros for an afternoon — this doesn’t mean that we don’t understand how the fashion world works, but we can’t do this.

We are also working on a brand family, so instead of being by yourself you can join other brands that have similar values. This would really open up the playing field for sustainable brands because they have the same problem everywhere. If we combine our budgets, let’s say from brands that offer non-competitive products such as sustainable lingerie or shoes, we can manage to do more things together.

We do have an online shop but our main goal is to have more stockists, because they are your ambassadors and are so important for the cities.

So, is this a model that already exists?

No, that’s what we’re working on.

I find really fascinating the capacity you have of going into things you have never done before or things that don’t even exist…

Well, time is on my side. When I started Good to Give and even when I started working in sustainability, around 1998, the term wasn’t on people’s minds.

Do you think that now it’s easier?

Yes, because I’m so used to swimming against the current and now the waves are all coming my way, so I can surf really easily.

I don’t have to explain anything. If I say to you it is ‘fair’ you know what it means. When I started, when I said ‘fair’ people were like: “What? Why?” Nobody knew what it was like and that’s why I think that fair trade is not enough anymore, it has to be fair chain. I want to know exactly where my wool is coming from — that’s why I want my own goats — and where my products are made. Because, at the end, our main goal is to bring economic perspective in these regions in Nepal.

But fair chain also means that you, as a consumer, have to be perfectly happy. Because when you pay €400 for a sweater, it’s wonderful that it is fair trade and animal-friendly, but you’re buying a sweater and you want it to be the best one you have. So I think our brand brings these two worlds together.

10 years ago, you bought it fair trade and you were OK with a less fashionable item.

When I started, when I said ‘fair’ people were like: ‘What? Why?’ Nobody knew what it was like and that’s why I think that fair trade is not enough anymore, it has to be fair chain.

That’s true, maybe a few years ago you would associate fair trade with crafty products.

Our end goal and challenge is to stay ahead of the troops. Because nowadays every brand talks about sustainability so it’s not a USP anymore. But, because I’ve been working in this field for so long and have so much experience, I think I have an indestructible optimism that has led us to where we are right now.

We just had our first presentation in Paris, with the tiniest showroom ever, so we could see how it works and it worked really well. We’re really happy.

As I told you, I wasn’t expecting this whole story behind the brand and it’s been really inspiring to hear all about it. Just to finish, what does sustainability mean to you?

It means durable, fair for all parties involved, without harming the ecosystem. And if it’s sustainable, it has to be lasting. Whatever you do, it has an impact on the environment, so you have to take measures to restore it or make it even better. That’s sustainability to me.

1. Some of the gifts available at Good to Give include jewellery, accessories and home items like ‘Bubble Buddy’, a soap tray and grater made of recycled plastic that can be used to grate soap and mix it with water, instead of using cleaning products sold with plastic packaging.

2. Cashmere was popularised in the late 18th century when the Kashmir shawl arrived in Europe and Queen Victoria and other royal members used it as a symbol of status and exotic luxury.

3. Chianti Cashmere Farm is the first cashmere farm in Italy and it was started in 1995 by American expat Nora Kravis.

4. Goats arrived in Australia in the 18th century with European settlers. In 1879, herds of goats roamed the streets of Sydney and police action was required in order to get them away.

5. The current fair trade movement originated in Europe in the 1960s, although in the 1940s and 1950s there were some attempts to commercialise fair trade products in Western markets by some religious groups and NGOs.

6. The B Corp Certification measures a company’s entire social and environmental performance. Some fashion B Corps include American womenswear label Eileen Fisher and outdoor apparel brand Patagonia.